Cooperation in the Port Sector from Japan to Indonesia

Unlike other archival materials, this report does not introduce a single project, but rather a history of more than 50 years of cooperation from Japan to Indonesia in the field of ports and harbors.

Since its inception as part of postwar reparations, cooperation in the port sector has continued uninterrupted to the present day, although the forms of cooperation have changed considerably with the changing times. During this period, not only individual port development projects were implemented, but also a wide range of efforts have been made in the field of port development policy, including the formulation of a National Port Policy and policy related management and operation by making full use of various tools such as dispatching experts, receiving trainees, development studies, financial cooperation, and loan financial cooperation.

This paper will introduce how these types of international cooperation have played an important role over the years in supporting Indonesia’s port development and ultimately its economic development, paying attention to the background and reasons for the changes in the content of such cooperation over the years.

Reasons for taking up this issue in the Archives

- 1)To review the history of cooperation in the port sector to Indonesia, which has continued for more than 50 years, and to look forward to the next generation of cooperation.

- 2)To introduce Japan’s various forms of cooperation (efforts combining various tools as well as individual development projects).

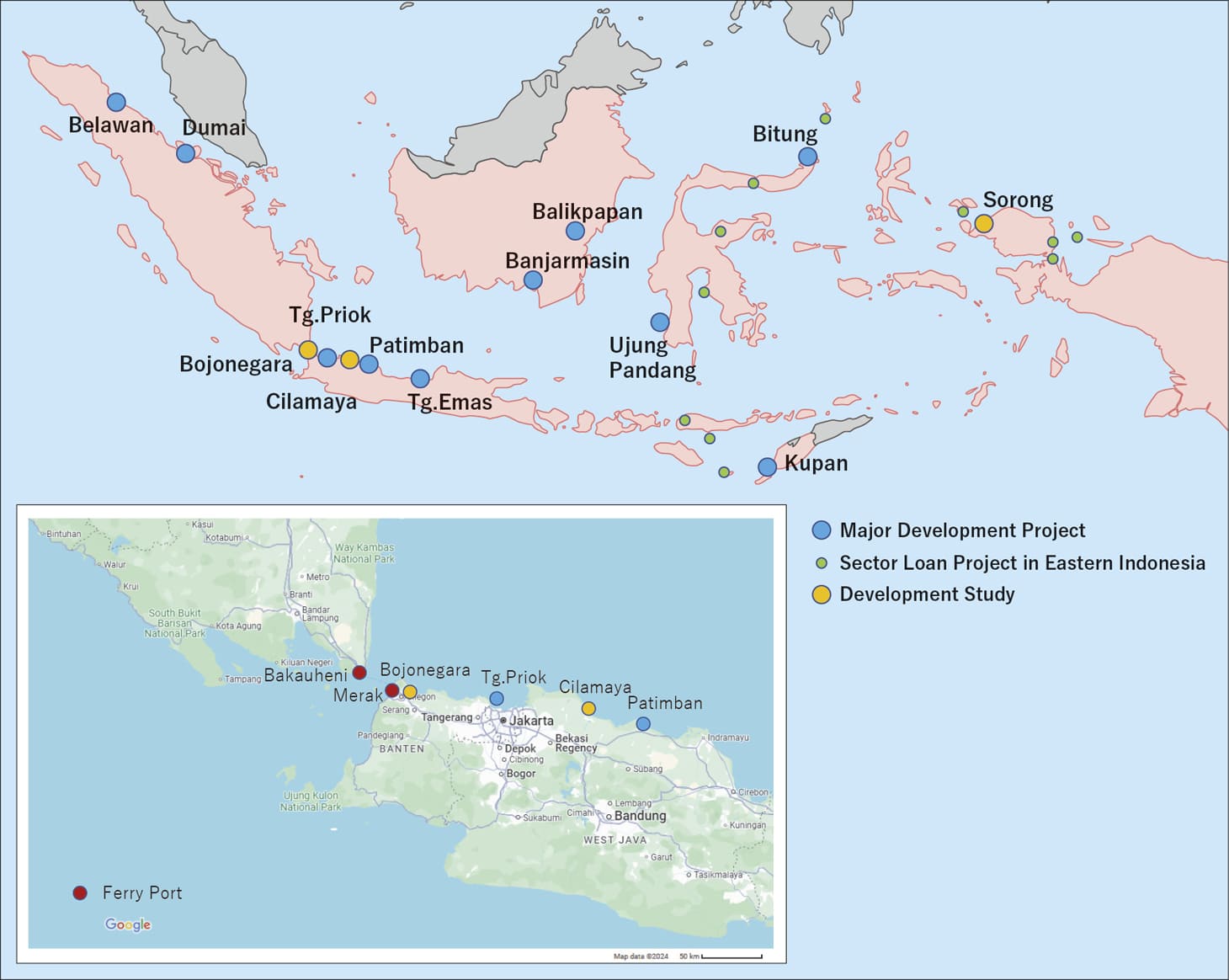

1Ports in Indonesia

Indonesia is an island nation consisting of more than 10,000 islands stretching about 5,100 km from east to west; in addition, three international straits are part of its territorial waters. The number of ports nationwide is about 650, and 28 ports have been designated as hub ports. (The number of hub ports has changed somewhat over time.) For the economic development of this vast island nation, it is extremely important to improve ports and harbors in each region, especially in remote areas such as eastern Indonesia, and to enhance port and maritime transportation.

These ports are under the jurisdiction of the Directorate General of Sea Transportation (DGST) of the Ministry of Transport, but an organization called Pelindo has effectively managed about 110 relatively large commercial ports for a long time.

In addition to these ports, there are ferry ports managed by the Directorate General of Land Transport of the Ministry of Transport that connect each island.

There is no port in Indonesia that can be called an international hub port. Various ports or locations were proposed as international hub ports in the past; Sabang Island located at the northwesternmost tip of Indonesia, Batam Island facing Singapore, Kuala Tanjung facing the Strait of Malacca, and Bitung Port located at the northern tip of Sulawesi Island.

2History of Japanese Assistance

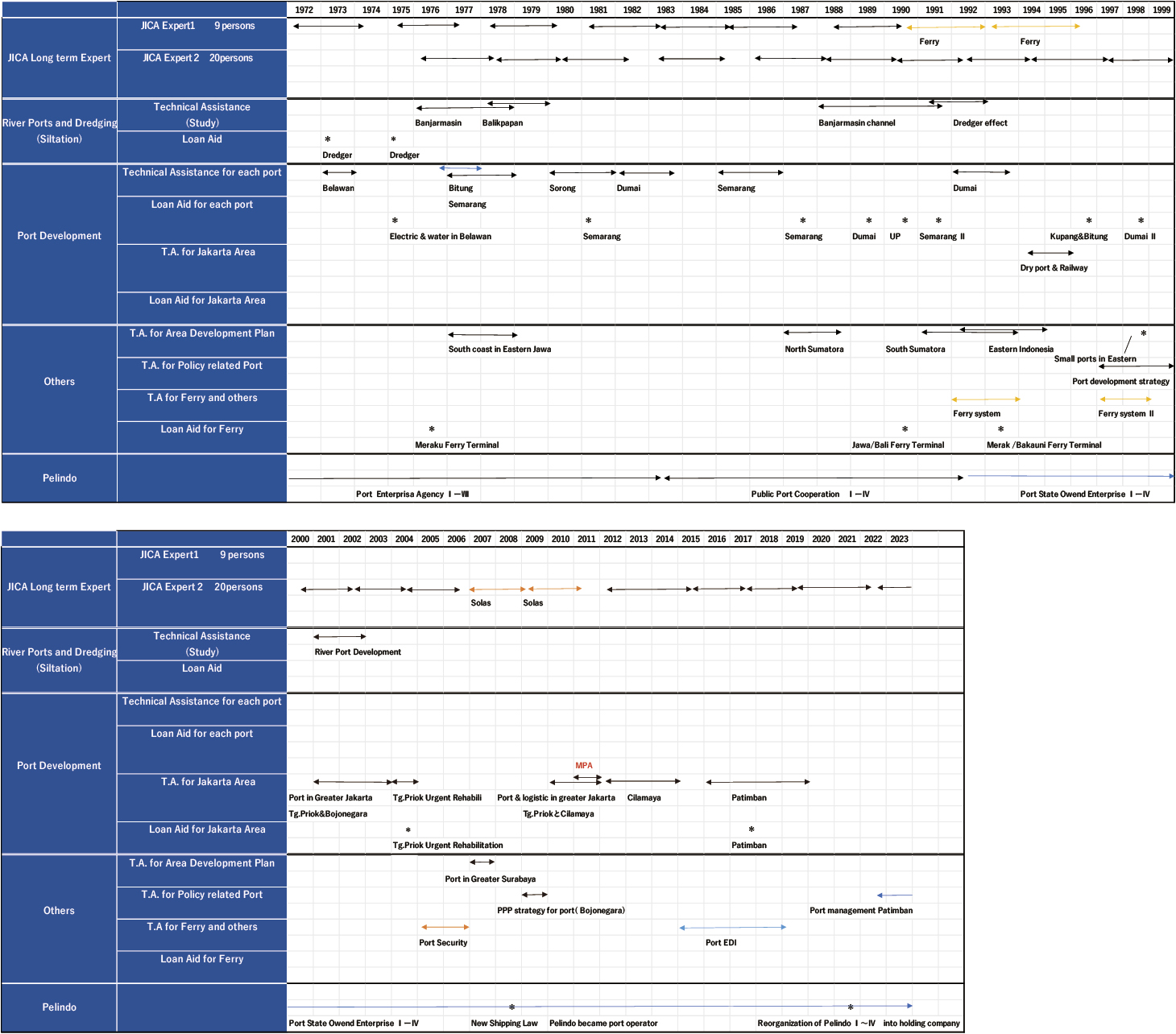

Japan’s international cooperation with Indonesian ports began in 1972 with the dispatch of JICA long-term experts, which continues to this day, and has focused on the implementation of various development studies and financial assistance. However, the content of this assistance has changed significantly due to the policies of both Japan and Indonesia, trends among other donors, and changes in the legal status and organization of Pelindo, which is now a state-owned port-operating company.

As a recipient country in the port sector, Indonesia is one of the most important countries in terms of its history, the number of projects, and their variety.

2.1Dispatch of Experts and Acceptance of Trainees

As of 2024, 27 long-term experts have been dispatched to Indonesia, and for the 20 years from 1976 to 1996, two port experts were stationed simultaneously. Although the experts initially focused on technology transfer in port engineering and construction methods in addition to project support, the proportion of project support work has gradually increased as time goes by. Two experts were dispatched to Directorate General of Land Transport from 1990 to assist with ferry port issues, and two experts were dispatched in 2006 to assist with issues related to SOLAS (The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea).

Not only port experts but also experts from the Japan Coast Guard, Bureau of Shipping, and Institute of Nautical Training have been dispatched to the Directorate General of Sea Transportation of the Indonesian Ministry of Transport, working together as the JMAT (Japan Maritime Advisory Team). However, only one port expert is dispatched to DGST now.

Since 1961, a total of 200 port-related trainees were accepted by JICA. The trainees came not only from the Port (and Dredging) Bureau of the Ministry of Transportation, but also from various regional offices, and even from Pelindo (although the names of these organizations have changed over the years). Apart from this long-term training program, many more Indonesians visited Japan for counterpart training for various projects, and through these exchanges, their understanding of Japan and Japanese assistance was deepened.

In particular, the Port and Harbour Research Institute of the Ministry of Transport (now the Port and Airport Research Institute) sent short-term experts to the Marine Hydrodynamics Laboratory of the Agency for Science, Technology, Evaluation, and Application (now the National Research and Innovation Agency, which centrally manages all research institutes) in Yogyakarta over the years and accepted many trainees. The two parties are continuing to collaborate on research and studies under a research cooperation agreement. The research themes are wide-ranging, focusing on tsunamis, siltation, and so on.

For example, the use of submerged dykes as a countermeasure against silting up of access channels and anchorage areas was studied in Kumamoto Port in Japan and Banjarmasin Port in Kalimantan in the late 1980s and was put into practical use in Kumamoto Port. In Banjarmasin, this countermeasure was not adopted, but it was put to practical use as a measure against siltation in the basin at the port of a private cement company near Surabaya by an exchange student from the Agency for Science, Technology, Evaluation, who was involved in the problem on a research basis at the time. Based on these experiences, the submerged dyke method is now being considered as one of the countermeasures against siltation of the access channel at Patimban port, which will be discussed later.

2.2Development Study and Loan Aid Projects

Japanese international cooperation to date, focusing on the target ports and fields, can be divided into three categories: “dredging and countermeasures for siltation of channels,” “development of regional core ports,” and “development of ports in the Jakarta metropolitan area.”

2.2.11970s (Japan’s Cooperation Initially Focused on Dredging and Countermeasures for Siltation of Channel)

In the 1970s, the World Bank mainly provided assistance to Indonesia’s main port, Tg. Priok Port while the Asian Development Bank provided assistance to Tg. Perak Port in Surabaya. As a result, Japanese assistance was mainly focused on areas outside of Java Island.

On the other hand, Indonesia has many river ports, mainly in Kalimantan, and maintenance dredging of navigation channels against siltation was a major problem. At first, “provision of dredgers” was the main form of assistance, and a series of development studies were conducted on measures against siltation of navigation channels and river ports.

From the late 1970s, studies began to be conducted on the development of regional core ports such as Bitung Port in North Sulawesi, Tg. Emas Port (Semarang) in Central Java, and Dumai Port in Central Sumatra.

Among these, development studies and loan-funded projects using Japan’s ODA were conducted several times for Tg. Emas and Dumai ports.

At Tg. Emas, a new container terminal was built, and a breakwater was constructed, followed by the expansion of the container terminal by Pelindo and the development of the surrounding industrial park. Tg, Emas has thus become a key port in Central Java.

Dumai Port was planned together with the development of industrial sites behind it and was developed mainly as a port specializing in palm oil exports. In addition to this function, the port is also used for the export of palm shells for biomass power generation.

2.2.21990s (Continued Development of Local Core Ports and Changes in Development Studies)

In the 1990s, in addition to the development of Tg. Emas and Dumai ports, the development of UjungPandang (Makkasar) and Bitung ports on Sulawesi Island and Kupang port on Timor Island was also carried out. The focus of these projects was the construction of container berths, and infrastructure development in rural areas, especially in under-developed eastern Indonesia.

During this period, JICA not only formulated independent port development plans, but also conducted a comprehensive study on ports and maritime transportation (“Study on Integrated Modernization Plan for Sea Transportation in Eastern Indonesia”), which was indispensable for the development of Eastern Indonesia, one of the Indonesian government’s policy goals. This led to the development of the Bitung and Kupang ports mentioned above.

Furthermore, two distinctive development studies were conducted by JICA.

The first was the “Master Plan of Container Handling Ports, Dry Ports, and Connecting Railways,” which called for the construction of an inland depot in Bandung and the use of railroads to address congestion at Tg. Priok Port. Similar to a study conducted in Laem Chabang Port in Thailand, a comprehensive study of the port and railroad sectors was conducted in Indonesia. Furthermore, this marked the first time that Japan had been involved in assisting Tg. Priok Port, which had been mainly supported by the World Bank.

The second project was a long-term policy study on port development in Indonesia. “The Study on the Port Development Strategy” which was conducted from 1997 to 1999 during the Asian currency crisis and the Jakarta riots, did not focus on individual port development or regional development as in the past but was intended to support the formulation of policies for all aspects of port development, management, and operation in Indonesia. The study covered a wide range of topics, including “the hierarchy of national ports handling containers and general cargo,” “the relationship between the government, Pelindo, and the private sector and financial resources,” “the port tariff system,” “privatization of port development and management,” “environmental protection,” and “maintenance of access channels,” and is believed to have influenced subsequent port policy in Indonesia leading to the enactment of new shipping law in 2008. Indonesia was the first country to conduct a study on port development strategy and it set a precedent for subsequent policy research in other countries, such as Turkey.

2.2.32000s (Beginning of Assistance for Ports in the Jakarta Metropolitan Area)

In the 2000s, Japan began to provide full-fledged support for the capital region’s port issues, including a development study of Bojonegara Port in West Java, which was planned in the 1990s to ease congestion at Tg. Priok Port. The study was conducted to expand the functions of Bojonegara Port, but the development of Bojonegara Port was suspended. In 2004, loan financial cooperation was provided for the Tg. Priok Port Emergency Rehabilitation Project, which included widening of the navigation channel and relocation of the breakwater. However, the actual construction work did not start until the 2010s.

2.2.42010 to the Present (Cancellation of the New Cilamaya Port Plan)

Since the beginning of the 2000s, Tg. Priok Port had become unable to cope with the rapid increase in containerized cargo and was facing serious problems such as an increase in waiting vessels and insufficient container yard capacity.

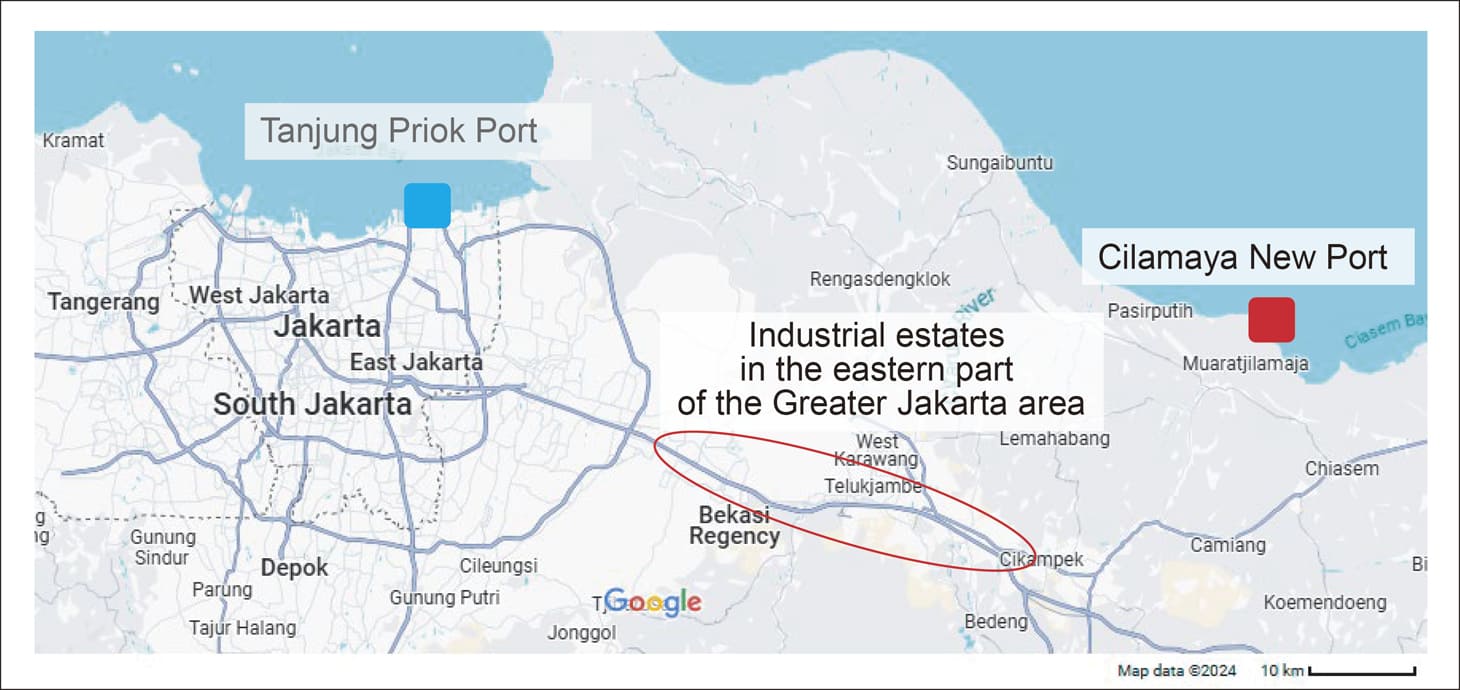

Furthermore, due to traffic congestion in the Jakarta metropolitan area, trucks could only make one round trip per day from an industrial park in eastern Jakarta, where many Japanese companies were located, to the port, instead of the required three round trips per day. The facilitation of logistics centering on the port became a major issue.

Considering this situation, the “Project to Develop a Logistics Improvement Plan for Ports and Harbors in the Greater Jakarta Metropolitan Area in Indonesia was conducted in 2010. As a result, two projects were proposed: the development of a new container terminal offshore of Tg. Priok Port and the development of a new port in Cilamaya, West Java.

The government of Indonesia accepted these two project proposals, and in May 2011, the two projects were included in the “Master Plan for Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia’s Economic Development.” The Cilamaya New Port Development was positioned as one of the five “flagship projects” in the “Jakarta Metropolitan Area Investment Promotion Special Area Initiative (MPA)” agreed upon between the Japanese and Indonesian governments in December 2010. The MPA was a framework for comprehensive study and monitoring of major issues in the Jakarta metropolitan area, the center of the Indonesian economy, such as subway development, sewage, and airport expansion, by the top levels of the two countries.

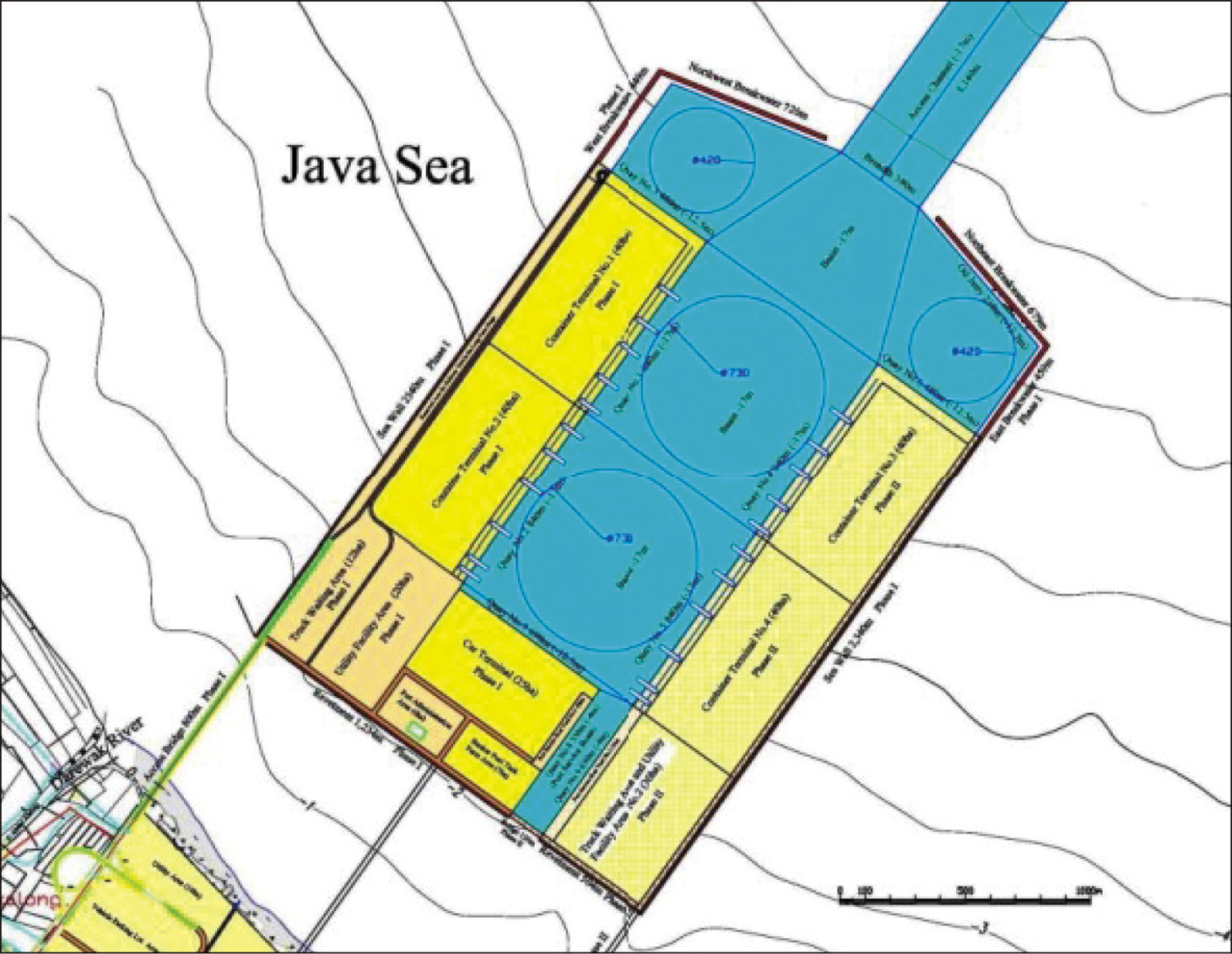

The Cilamaya New Port Development was to build a car terminal and container terminal 80 km east of Jakarta, mainly for the purpose of transporting finished automobiles and containers from and to the industrial parks in eastern Jakarta.

The location and layout of the facilities are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

However, the following objections from within Indonesia were lodged in response to the Cilamaya New Port Project.

(1) Opposition to the Access Road Plan from the Ministry of Agriculture

The Ministry of Agriculture expressed support for the development of Cilamaya Port itself but objected to the new access road which would pass through a paddy field area for about 30 km, which the Ministry argued would jeopardize food security.

In response, the Japanese consultant changed the original plan from a road through rice paddies to an elevated road along a canal several kilometers to the west, and prepared a plan for a new railroad line to the port, which was strongly requested by the Ministry of Transport’s Railway Bureau, by building a road and two stories on the same legal line.

(2) Opposition from Pelindo2

Although Pelindo2 had initially strongly requested the Ministry of Transport to participate in the development and operation of Cilamaya, the Ministry did not accept the request. There were two reasons for this. The first was shipping companies and other users were opposed to Pelindo’s autocratic port management. The second was the Ministry wanted to remove Pelindo’s monopoly right to manage and operate ports as stipulated in the new Maritime Law of 2008, taking advantage of an opportunity of a major greenfield port development.

In response, Pelindo2, which obtained the North Caribbean development rights for the planned expansion of Tg. Priok Port, sought to delay the progress of the Cilamaya Port development by insisting that the agreement include a provision that “no new container terminal will be developed within 150 km around the port for a certain period.”

In response, JICA explained to the Indonesian government that the Tg. Priok Port expansion plan and the Cilamaya port development are compatible in terms of container demand, and that traffic congestion to and from the hinterland and concentration of traffic in Tg. Priok Port are undesirable.

(3) Objection from Pertamina

After the location of Cilamaya was determined, Pertamina, a state-owned oil company, submitted a claim that the location of Cilamaya overlapped with the planned location of new oil resource development, and the location of the port itself was hastily adjusted by shifting it about 3 km to the west. However, a major opposition movement subsequently emerged, claiming that the access channel would cross an offshore pipeline and be near an offshore drilling rig, thus risking collisions by vessels and damage to the pipeline.

In response, JICA conducted a risk assessment analysis using independent overseas consultants (Booz and Company, DNV GL, Mot MacDonald), and after comparing the results with similar cases in other countries, concluded that there would be no major problems if measures such as stone cage matting were taken for the pipeline directly under the access channel.

However, in April 2015, the Vice President visited the site and made a formal decision to “reexamine the location with a blank slate” due to conflicts with oil-related facilities, and the Cilamaya port development plan was forced to be suspended.

2.2.5Launch of the Patimban New Port Project

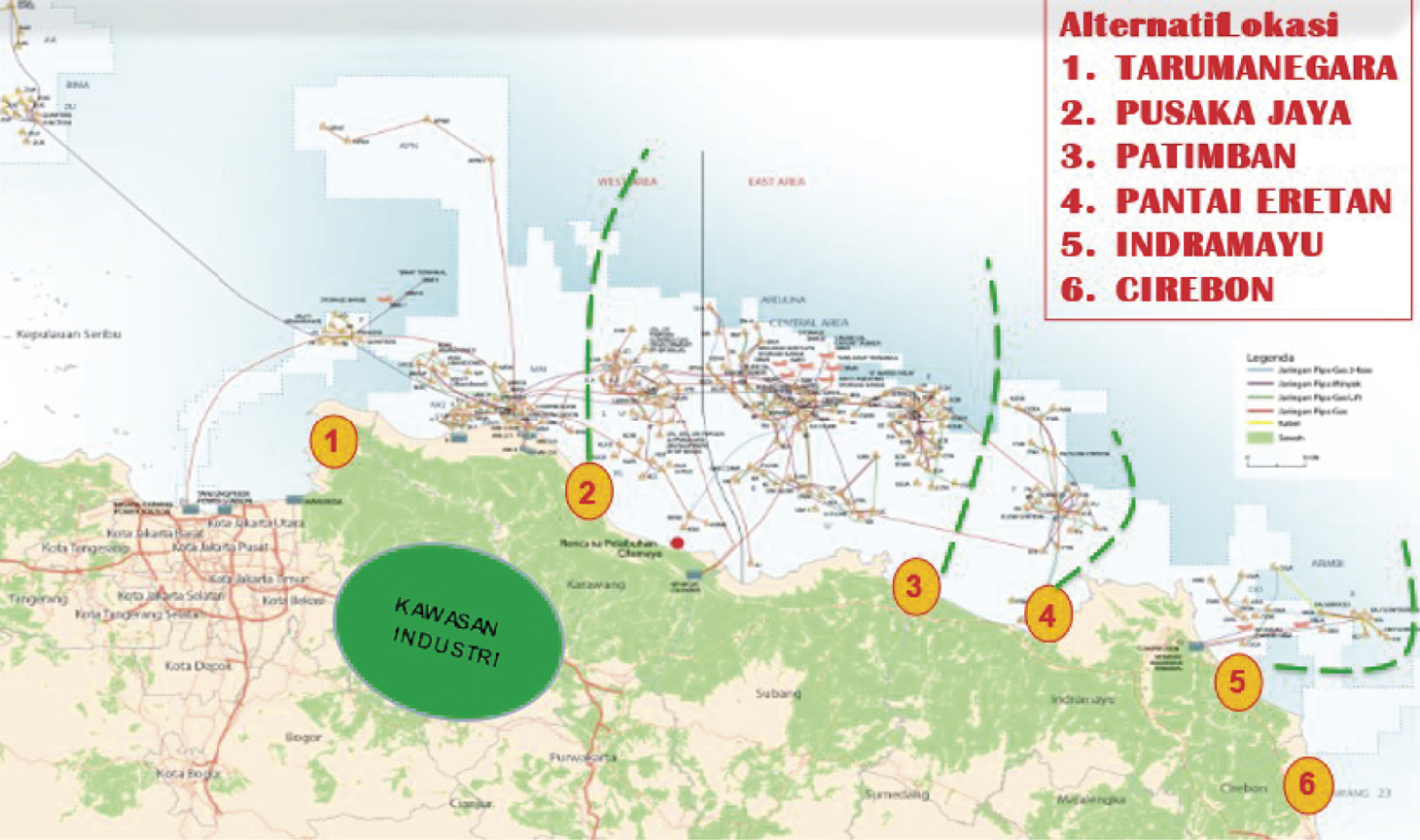

Two weeks after the Cilamaya Port Development Plan was cancelled, a meeting was initiated within the Indonesian Ministry of Transportation to select a new candidate site. Comparisons were made focusing on the relationship among the access channel plan and the oil and gas development plan, as well as the time and transportation costs from the industrial parks.

Subsequently, the Indonesian Ministry of Transport conducted a study from August to December 2015 to select a candidate site and selected Patimban (Figure 5, #3) as the site for the new port, and in 2016, the Indonesian government again requested support from the Japanese government.

Patimban is located 40 km east of Cilamaya and 120 km from Jakarta. Once again, Japan was responsible for formulating its draft plan, and based on this plan, the Indonesian Ministry of Transport decided on a master plan in 2017. The facility plan is almost the same as that of Cilamaya, but this was because after the cancellation of the Cilamaya port development plan, only minimal surveys were conducted to develop the new port in the shortest possible time, even if the location was changed.

In November 2017, the first phase of Phase 1 yen loan contract, worth 118.9 billion yen, was signed, and construction of breakwaters, seawalls, one berth for a car terminal, dredging of the navigation channel and anchorage, and an access road from the existing national road began in 2018.

Most of these works were ordered as STEP (Special Terms for Economic Partnership) projects under Japanese ODA, and to make up for the delay in the project, rapid construction was carried out using the “Straddling Method” for the quay wall, the “Pipe Mixing Method” for soil improvement of reclaimed sand, and the “Deep Mixing Treatment Method” for improvement of the original ground.

The car terminal was put into service at the end of 2021, and currently about 20,000 finished automobiles are imported, exported, and transferred per month.

In May 2022, a 70.1 billion-yen yen loan contract for Phase 2 was signed, and in October of the same year, work began to increase the depth of the navigation channel from -10m to -14m, while automobile terminal will be expanded from one to two berths, and two new container berths will be constructed. The same construction methods used in Phase 1 are being applied in Phase 2, which is being carried out by a Japanese company as a STEP project. This work is expected to increase the capacity of the car terminal and put the container terminal into operation.

While previous financial assistance for ports in Indonesia has amounted to a few billion yen for each port, the total amount for the Port of Patimban is an order of magnitude larger, amounting to about 200 billion yen.

In addition, to drastically improve access from the port to the surrounding industrial park, a highway from the existing highway to Patimban Port is being developed through a PPP scheme as well as Japanese ODA and is expected to be an indispensible infrastructure for the container terminal of the port.

2.2.6Participation in Terminal Operation

KSOP, a regional agency of the Ministry of Transport, is the administrator of the port. In March 2021, an agreement was signed between the Indonesian Ministry of Transport and PT. Pelabuhan Patimban International (PPI), a consortium of four local companies. will select and contract the operator of the car terminal and container terminal, and at present, the car terminal is operated by “PT. Patimban International Car Terminal (PICT), a company in which Toyota Tsusho Corporation, Kamigumi, NYK Line, and Toyofuji Shipping Co., Ltd. have equity stakes.

A container terminal operator has not yet been selected as of June 2024.

2.2.7The Project for Capacity Development on Port Management Organization in Indonesia

Patimban Port is the first international commercial port that is effectively managed without Pelindo by the Ministry of Transportation as the port administrator.

Therefore, in view of the need to provide various support to the port manager, a technical assistance project was launched in March 2023 to improve the management and operational capacity of the port manager of the Port of Patimban.

The project aims to facilitate the smooth development of Patimban Port by providing basic port management policies and methods to the port manager of the Ministry of Transport, who will be managing the port for the first time in the absence of the Pelindo organization, which plays a major role in the management and operation of other major ports.

3Changing Trends in the Field of International Cooperation and Future Prospects

3.1Relationship between Pelindo and the Ministry of Transport

The changes in the content of international cooperation are based on “trends among other donors,” “the Indonesian government’s policy on overseas financial assistance,” and “Japan’s aid policy,” but the “changes in the structure of Pelindo, one of the main actors in port development and management in Indonesia, and its relationship with the Ministry of Transport” are also thought to have had a significant impact.

Pelindo was originally established in 1960 as a state-owned company to develop and manage commercial ports in eight locations throughout the country and was subsequently consolidated with the port management functions of the Ministry of Transport.

In 1983, Pelindo was integrated into four port corporations, and in 1992, it was transformed into a state-owned port company. Today, Pelindo is integrated into one nationwide port operating company.

In the beginning, employees of the Ministry of Transport were given Pelindo status as well, and the two organizations frequently exchanged personnel, with the Ministry of Transport controlling the budget and personnel rights. Furthermore, the financial situation of each Pelindo was never good, and until around 2000, the development of regional core ports was promoted by the Ministry of Transport using overseas loans, while Pelindo managed the developed ports.

However, after 1992, personnel exchanges ceased, and gradually the personnel and budget authority of Pelindo executives were transferred from the Ministry of Transport to the Ministry of State Enterprises, which was established in 2001. Under the leadership of the Ministry of State Enterprises, each Pelindo became capable of securing ample budgets by using its own funds, borrowing from city banks, and issuing bonds to carry out port development on its own.

In 2008, a new shipping law was enacted and port managers from the Ministry of Transportation were established at each port, while Pelindo was positioned as the port operator, and the sense of unity between the two organizations gradually faded away.

3.2Recent Trends in Port Development and Future International Cooperation

In recent years, the development of not only the capital Tg. Priok, but also regional ports such as Belawan, Kuala Tanjung, Tg. Emas, Tg. Perak, Makkasar, and other ports have all been conducted by Pelindo and private operators. The Indonesian government has a policy of not using the national budget or foreign loan funds for new port development in the future and has requested that core ports that Pelindo has no intention of developing be “developed by Japanese companies through a PPP scheme.”

Recently, the Ministry of Transport has set up a PPIT (Transportation Infrastructure Financing Center), an organization specializing in the financing of various projects, including those funded by the private sector. In the case of Anggrek Port in North Sulawesi, a concession contract was signed between a private company and the Ministry of Transport. As with Patimban Port, the private sector is entrusted with the management of the port, including the extension of the quay wall. However, most of the PPP projects in many other ports have not been subjected to feasibility studies and are not necessarily attractive to Japanese companies.

Under these circumstances, for the time being, it will be necessary to continue to support the development, management, and operation of Patimban Port, while paying attention to trends in regional port development such as large-scale port development to create an international hub port, and port development related to the relocation of capital functions, etc. It will also be necessary to monitor the participation of Japanese companies in PPP projects and cooperation with Indonesian private companies in the form of loans.

4Significance of Japanese Assistance and Exchange in the Indonesian Port Sector

As described above, the relationship between Indonesia and Japan in the field of ports and harbors has continued uninterruptedly for more than 50 years. While the contents of cooperation have changed over time, it covers a wide range of areas, including research, technology transfer, port and regional development planning, long-term planning and port policy, implementation of individual projects, and financial assistance, covering the entire country of Indonesia. It is believed that Indonesia is the only country where Japan has continued such extensive and long-term international cooperation in the field of ports and harbors. This includes the dispatch of long-term experts which has continued uninterrupted for a long period of time. Over the years, the Indonesian Ministry of Transport has accepted many long-term experts in the fields of aviation, railroads, shipbuilding, coast guard, and seafarer training, but at present only port experts are dispatched.

This can be seen as an indication of the expectation and trust that the Indonesian Ministry of Transport has in Japanese assistance in the field of ports and harbors. Not only the expectation of financial support for projects, but also the strong sense of responsibility in Japan and the long-standing ties and bonds between organizations and individuals have fostered overall trust, which has not only had a significant impact on the long-term vision for ports and port administration but has also led to the continuation of good relations.

These connections resulted in Indonesia joining PIANC (World Association for Waterborne Transport Infrastructure), a forum for technical cooperation on international water transportation infrastructure in 2015, and PIANC-Japan’s vigorous cooperation in strengthening the PIANC-Indonesia structure in 2024.

In addition, JOPCA (Japan Overseas Port Cooperation Association), a Japanese private volunteer organization, is planning to resume in 2024 exchanges with Alumni who have completed port-related training in Japan which were suspended due to COVID-19.

Although there are no immediate plans for a project to follow the current financial assistance for Patimban Port, there are expectations for Japanese companies to participate in PPP projects and requests for Japanese technical assistance on the soft side. Even as Indonesia gradually becomes less dependent on financial ODA, it is expected that cooperative relations based on trust between Indonesia and Japan in the port sector and ties between port managers will continue in the future.

5Lessons Learned

(1) In addition to the implementation of individual development projects, the Japanese side has also assisted in formulating a long-term policy for ports, and cooperated in the development of Patimban Port from the planning stage to the operation phase, thereby establishing deep ties between Indonesia and Japan in the field of ports.

(2) By combining various tools such as the dispatch of experts, counterpart training, the implementation of development surveys as well as providing grant aid, Japan has contributed to the development of Indonesian ports which in turn have supported the economic development of Indonesia.

Author

Hideo Sasaki

Overseas Coastal Area Development Institute of Japan (OCDI)

Born in 1958, Sasaki graduated from Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1980 and worked for the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (ex. Ministry of Transport) from 1980 to 2018 and has been working for Tomakomai Port Authority as Executive vice President and OCDI.

Sasaki was dispatched to Indonesia as JICA expert for port planning, 1994-97 and 2012-15